- Home

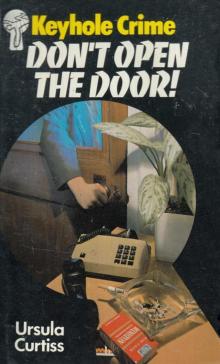

- Ursula Curtis

Don't Open the Door

Don't Open the Door Read online

Even if her neighbors had believed Molly Pulliam’s incoherent story of something hiding behind the lilac bush, it would have made no real difference in the end. Eventually she would have opened the door to her deadly visitor.

Her murder rocked the quiet valley community. Unlike an occasional stabbing in a bar in downtown Albuquerque, this tragedy came frighteningly close to home. The Sheriff’s officers, however, had no reason to question the very small boy who was visiting his cousin Eve Quinn, and it would have helped him if they had.

Eve, a slender fair-haired girl, was too preoccupied with getting over a disastrous engagement to wonder what, the mysterious treasure was that Ambrose wanted her to get for him in the toolshed, or why the usually indeflectible little boy wouldn’t go into the shed himself. And so the killer, driven by his twisted hate, was free to knock on another door, to greet another victim.

This is the beginning of an absorbing novel of secrets new as well as almost forgotten, and of murder hiding behind a familiar face.

DON’T OPEN THE DOOR!

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Also by Ursula Curtiss

DANGER: HOSPITAL ZONE

OUT OF THE DARK

THE WASP

THE FORBIDDEN GARDEN

HOURS TO KILL

SO DIES THE DREAMER

THE FACE OF THE TIGER

THE STAIRWAY

WIDOW’S WEB

THE DEADLY CLIMATE

THE IRON COBWEB

THE NOONDAY DEVIL

THE SECOND SICKLE

VOICE OUT OF DARKNESS

DON’T OPEN

THE DOOR!

URSULA CURTISS

DODD, MEAD & COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright © 1968 by Ursula Curtiss

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without permission in writing from the publisher

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 68-29806

Printed in the United States of America

by Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., Binghamton, N. Y.

DON’T OPEN THE DOOR!

1

EVEN if anybody had believed Molly Pulliam it would have made no real difference in the end. She might have been allowed one more appointment with her hairdresser, or a last afternoon of bridge, or a final fitting of the pink tweed suit she would never wear, but her imminent death was quite a settled thing.

As it was, no one did believe her; not her husband Arthur, nor her sister Jennifer—certainly not the Hathaways, who had been regarding her with a certain reserve ever since. Gradually, a little abashedly, Molly fell in with the general theory of one cocktail too many, the extravagantly high heels she was wearing, a trick of the almost-dusk.

She had been walking home from the Fletchers’ cocktail party, a gathering which managed to be both noisy and dull; in addition, she had been on one of her intermittent starvation diets and her two whisky sours were surprising to a stomach lately accustomed to nothing more rakish than carrot strips or a spoonful of cottage cheese. On all counts it seemed desirable to leave. Molly made unobtrusive farewells, refused a ride and let herself out into the end of the late-September day.

It was a bare half mile home along the winding road, but her silky sheath and pumps were not designed for rapid walking. By the time she was nearing her own driveway, marked at one corner by a huge lilac, the sunset dapplings had been swallowed up in dark chiffon light. What a delight it was going to be simply to get unzipped, thought Molly—and the lilac stirred in the utterly still air, and swelled.

In a twinkling, all her senses were engulfed in panic; it was as though some fearful warning had been shrieked at her through the twilight. Involuntarily, knowing only that she must get away from here, Molly began to run.

Her slender high heels and the gravelly road edge betrayed her. In one instant she had her eyes fixed wildly on the lights of the Hathaway house, down and across the road; in the next, she was picking herself up, crying soundlessly, her palms stinging like fire. She had lost one shoe when she fell; she paused fractionally to wrench off the other, with the result that when the Hathaways’ door opened under her frantic pound mg she was dusty, tear-streaked, and barefoot.

Wizened little Mr. Hathaway said in horror, “Mrs. Pulliam!” and then gave a practiced sniff. He suggested warily to Molly that perhaps she had better, er, sit down, and he called his wife.

Mrs. Hathaway, a large woman who looked like a block as yet unattacked by a sculptor, had a nose every bit as keen as her husband’s. She cast him a significant glance before she said to Molly, “Has something happened, Mrs. Pulliam? Are you all right?”

Molly was still laboring to regain her breath, still weak with reaction at the fact that there were people and lights and a door between her and that terrible swelling in the lilac. She said gaspingly, “There’s someone out there, there’s someone hiding in— I was just about to turn in at the driveway and there’s no wind at all—”

Drinking, commented the Hathaways’ compressed lips and steady inventory of her nyloned toes and dirt-smudged face, but in the end Mr. Hathaway volunteered to escort Molly home. He made a preliminary excursion with an enormous flashlight; all it turned up was Molly’s pumps.

“I’d have a cup of nice hot soup if I were you,” said Mrs. Hathaway in a tone she evidently considered diplomatic as she ushered them out; there was a suggestion that she would spray air-freshener about as soon as Molly Pulliam and her whisky sours had left.

It was now completely dark outside the brilliant scope of the flashlight, but even for Molly the menace in the lilac was gone. It had been there, and it had removed itself. Nevertheless, she was grateful for Mr. Hathaway’s meticulous room-by-room inspection of the house as she turned on lights and drew curtains and made sure the doors were locked.

Departing, he said, “Will your husband be away for long?”

“No, thank heavens, he’s coming home tomorrow.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Hathaway profoundly. “Well, I imagine you’ll be all right now, Mrs. Pulliam. You probably heard a dog—”

“Dogs aren’t tall,” said Molly flatly, and Mr. Hathaway, unable to controvert this statement, bowed slightly and took his departure.

Molly went at once to the telephone. Jennifer and her husband, Richard Morley, had often invited her to spend the night when Arthur was away, and their guest room would never be more welcome.

The Morleys’ phone did not answer.

They’ll be home in a few minutes, thought Molly resolutely, and made preparations for her dinner and changed her clothes and tried the number again, without success. But the feeling of necessity was ebbing fast; the house was securely locked, after all, and whoever had concealed himself so quietly in the dusk had no way of knowing that either she or the Hathaways had not called the Sheriff.

Molly was seldom too shaken to eat. There was cold chicken in the refrigerator, and she made herself a generous sandwich—this hardly seemed the moment for dieting— and presently went to bed. Already dimming in her mind, because she was not an imaginative person, was the inevitability of certain natural equations, like lightning preceding thunder.

Arthur Pulliam came home the next day. He listened to Molly, said, “Really?” and listened to the Hathaways and said, “Really!” in a very different tone.

Je

nnifer Morley, as lean and dark as Molly was rounded and blond, said, “Face it, you haven’t the world’s greatest head for liquor, and the Fletchers’ parties would send anybody around the bend. Granted there was somebody behind the lilac, don’t you think it was boys, just out after mischief, and they got scared off? Remember the robbery the Armstrongs had, and that was in broad daylight.”

Boys. Seeing the carport vacant and the windows dark, assuming that the house would be empty for the evening, starting guiltily in the hollow-centered old lilac so that it had changed its shape in that frightful way . . . It was a reasonable and even a graceful explanation, and because Molly was optimistic by nature and usually held the convictions of the person she had talked to last, she accepted it.

She was not even faintly nervous on the evening of October tenth.

“Going to be all on your own tonight, hon?” Iris Saxon folded the last of the beautiful weekly ironing and gave Molly a fond and roguish wink, startlingly girlish in her severe, wrinkle-netted face. “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do.”

“Well, with me you never know,” said Molly in the same tone, and Iris laughed, cocked her head at the sound of a car in the drive, said, “There’s Ned. See you next week,” and let herself out.

Molly was guiltily relieved that Iris’s husband had not had time to come to the door for her. For some reason she had a sense of acute embarrassment with Ned Saxon, perhaps bound up in the fact that, out of work himself, he was collecting his gentle elderly wife from her job. Ned, possibly aware of this, seemed to enjoy pinning Molly down relentlessly on subjects she knew next to nothing about, with the result that she had to listen helplessly while he reconstructed foreign policy or told her what the junior senator was really up to with that farm bill. These sessions were frequently conducted in the windy open doorway while Molly’s hair spun in her eyes, or it was well below freezing and she was clutching a sweater about her.

But tonight that had been avoided. Although Molly would not have admitted it, she rather enjoyed Arthur’s absences from home. She had her bath early then, changing into a housecoat and slippers, and ate what she pleased for dinner while she watched something unimproving on television. After dinner she could stack the few dishes in the dishwasher, arrange the pillows in the bedroom and read until three in the morning if she felt like it without disturbing a soul.

By the time she had had her bath, on this evening, the windows were dark. Unlike many women in a house fairly well isolated in its own grounds, Molly was not nervous alone at night. She did the obvious things, like locking the doors and drawing the curtains, but she did not people the closets with faceless assailants or imagine the faint creak of tree branches to be some stealthy approach from outside.

She had put on spareribs to simmer—something both Arthur and Jennifer would have disapproved heartily—and poured herself a small glass of sherry when the telephone rang.

“Hi,” said Jennifer’s crisp energetic voice. “How would you feel about being picked up for dinner now that Richard’s been called out to show a house and we’re both left flat?”

“Oh, I’m in my robe and I’ve got things started here. I don’t think—”

“Unstart them,” said Jennifer with the unconscious authority of being five years older. She added alluringly, “I’ve got lobster.”

Molly hesitated, and the bubbling spareribs, which had now been joined by sauerkraut, sent out an enticing whiff.

All that remained was to make dumplings. She said, “Thanks, Jen, but I’d really rather stay in,” and lightly, carelessly set the time of her own death.

There was a swishy wind around the house, a cold autumny sound which made the lamplight and tranquil pretty living room that much more attractive. Molly finished her sherry, watched a panel show which Arthur would have denounced with an angry rattling of his newspaper, and was beating the dumplings when there was a knock at the back door.

Molly paused in surprise, chattered the spoon against the edge of the mixing bowl, and opened the door that led into the small utility room. She was not foolish in spite of her sunny confidence; she switched on the outside light for a look at this unheralded visitor before she went to the back door itself.

Radiance showered down on the familiar creamy-orange head. Molly twisted the lock at once and opened the door; she said perplexedly, “Oh, did you come—?” and then, because of some quality of the silence, her glance dropped to the idly swinging right hand that held the hammer, its head muffled in rags.

She ran. Informed by perhaps the second moment of perfect knowledge in her uncomplicated life, she knew that this had waited for her ill the lilac, that she had let it in, that it was now in the house with her and following her with speed and purpose.

She screamed like a child, twice.

2

THE brutal and apparently senseless murder of Molly Pulliam rocked the quiet Valley. Unlike the occasional stabbing in a bar in downtown Albuquerque, or the predawn bullets with which estranged husbands and wives estranged each other permanently, this came close in every respect. It had an appallingly cosy, this-could-happen-to-you atmosphere.

The very domesticity of the setting was shocking. People who dealt in drugs, or regularly gave all-night parties, were never far removed from the risk of violence—but here there were spareribs and sauerkraut burning on the stove while dumpling batter waited in a mixing bowl. Again, multiple divorcees often had multiple enemies among both sexes, but this victim was a cheerful pretty wife of fifteen years’ standing.

Moreover, Molly Pulliam, alone in the attractive adobe house, had not been the only vulnerable target in the area on that particular night. Not a mile away Vera Paget was also watching television while her psychiatrist husband spoke at a banquet at a downtown hotel; within the same radius elderly Mrs. Heinemann knitted drowsily while baby-sitting for her son and daughter-in-law. Both carports were empty, both homes would have looked equally promising to a burglar.

That the original intention had been robbery seemed inescapable. There was the smashed pane in the back door, the sound probably covered by the television program in progress in the living room, through which the intruder had only to stretch his hand and twist the lock. There was Molly Pulliam’s emptied pocketbook, the small possessions scattered on the floor and the wallet missing. Molly Pulliam herself lay face-down in the doorway between kitchen and dining room, in a convulsive position although the first terrible blow to the back of her head must have killed her. There had been successive blows.

Although Richard Morley, the dead woman’s brother-in-law, had apparently used his head when he arrived on the scene at a roughly estimated hour after the murder—he had turned off the gas under the reeking dinner but touched nothing else—the case had an air of failure from the start. The autopsy declared the weapon to have been a hammer or other implement with a circular edge, wielded with extreme force, but no weapon was found. Fingerprinting was done, routinely and unrewardingly. Footprints were never even a hope: there had been no precipitation for six weeks and the ground was wind-scoured almost to the consistency of stone.

Jennifer Morley, eyes burning and voice ragged as she fought the sedatives she had been given, told them of her sister’s recent experience and there was a brief spurt of interest in the huge old lilac. Inspected minutely, it yielded a cracked pink plastic spoon, a few ancient scraps of paper, and the mummified skin of half an orange. Nevertheless, Sheriff’s officers dutifully questioned the Hathaways, who agreed that Mrs. Pulliam had certainly seemed very frightened but had been—here their glances dropped repressively while their eyebrows went up—“tired and not really herself” at the time.

“What I don’t see is why,” Jennifer kept saving to Richard, to Arthur Pulliam, to the investigating officers. “Molly would have been frightened to death of a burglar, she wouldn’t have resisted him for a minute. She’d have handed over her purse and anything else he asked for, like—like bank tellers and people in stores when there’s a holdup. Why did

he have to kill her?”

Panic, the deputy told her. Prepared for a burglar, Molly Pulliam might have acted as sensibly as her sister thought; coming without warning on a stranger who had forced his way into her home at night, she had much more probably screamed and run, triggering an answering panic and a wild violence in the intruder. The deputy did not add that this argued an amateur criminal, which would make him that much harder to find.

Nor was he aware, because he knew the Morleys only by sight from his routine patrols of the Valley, of the strange gulf between husband and wife. He saw the comforting grip of Richard Morley’s hand on his wife’s shoulder and could not know that her muscles had stiffened; he saw her wan upturned smile and could not know how it made her mouth ache.

Because Jennifer would not put it into words. Although she and Molly had been closer than many sisters, she had turned, after the first incredulous grief, into a woman operating by remote control. In spite of Tier basic dislike of Arthur Pulliam she had insisted that he stay with them through the first forty-eight hours of shock, and she had been attentive to his diet. She was calm even through the massive descent of Arthur’s relatives from Wichita, all of them breathing camphor and disapproval from every pore. All other members of the family, the r manner made clear, died in hospitals and had the best of attention before the end.

Jennifer, already rubbed too raw for any reaction as strong as amazement, realized with dim wonder that Arthur was absorbing some of this; mingled with his grief there was now an air of petulance. “I really don’t think,” he observed to the company at large, “that the newspapers need have made so much of the—details of the dinner preparations.”

Bald male and frizzled female Pulliam heads moved ponderously in assent. “A little pheasant and some fresh asparagus would certainly have looked nicer,” remarked Jennifer, dangerously quiet as she rose and left the room, but that was the only liberty she allowed her stretched nerves.

Don't Open the Door

Don't Open the Door