- Home

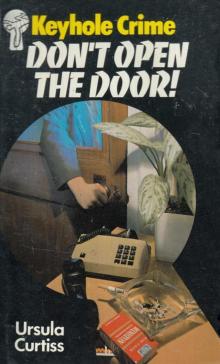

- Ursula Curtis

Don't Open the Door Page 2

Don't Open the Door Read online

Page 2

When Richard, following her into the kitchen, said in a low voice, “Jen, for God’s sake! I know you keep thinking—” she raised her eyebrows politely at him. “What I keep thinking is that all those—people, would you call them?—have planes and trains to catch very soon, so if you’d give me a hand with this coffee . . .”

She refused, steadfastly, to discuss a period on the evening of Molly’s death. After her own solitary dinner she had settled down to work on the beige cable-stitched sweater she was knitting for Richard’s birthday. She reached the armholes, counted stitches perplexedly, and went in search of her instruction book before remembering that she had lent it to Molly.

At once the sweater assumed an imperative nature, although Richard’s birthday was still four weeks off, and knitting seemed the only possible way to pass the time until he got home. When Molly’s telephone did not answer, Jennifer thought idly, She’s in the tub. She made herself a second cup of coffee and tried again, and was hanging up, frowning, when Richard arrived.

He looked tired and irritable. There must, he said, be a special corner of hell reserved for people who made an appointment with a real estate broker—an evening appointment at that—and then failed to “show up.’

Jennifer sympathized, somewhat absently. She dialed the Pulliam number once more, waited, and put back the receiver; her frown had deepened. “I wonder where in the world Molly is? Richard, if I make fresh coffee while you’re gone, would you just drive over and check?”

Richard expostulated. He had just climbed out of his car; he was tired after the day, the dinner that had consisted of a snatched hamburger, the futile vigil in that damned empty house. Molly was a grown woman who might have a dozen good reasons for not answering the phone at the moment; just what was Jennifer imagining could have happened to her?

His brisk impatience ought to have made Jennifer feel foolish, but it did not. She wasn’t so much worried as baffled and annoyed at the total strangeness of the situation, and she said crisply, “Well, I’ll go, then, but you’ll have to give me your keys. I’ve just remembered that I’m almost out of gas.”

Richard gave her a wry look—they had both known all along that he would go—and poured and drank a cup of coffee with perverse deliberation before he departed.

How many minutes lost there? Had a gloved hand been reaching in for the back door lock, had Molly been screaming with terror while they stood and debated in their kitchen? Logic would presently tell her no, but after only three days logic had a very small voice indeed . . .

While the Sheriff’s officers questioned known robbery-with-violence offenders, the frightened Valley took its own steps. Although in this country most householders owned a gun and most wives knew how to handle it, the three local hardware stores quickly ran out of heavy bolts and chains, and the animal shelter was emptied of its large-dog population. Children ordinarily allowed to roam were planted sternly before television sets; instantly they developed a hatred of television, fraying their mothers’ nerves to the point where all door-to-door salesmen and innocent meter-readers were reported to the Sheriff’s office as, “There was something very suspicious about that man, Officer. I think it was his eyes. You could tell he wasn’t normal.”

There was certainly no reason for anyone to question a very small boy at 159 Allendale Road, and it would not have helped if they had.

3

“I THINK,” said Iris Saxon, glancing up from the ironing board in Eve Quinn’s small kitchen, “that the little boy is doing something to your chrysanthemums.”

Eve put down the letter she was reading and stifled a sigh. Although her young cousin Ambrose had been visiting her for three weeks now, Mrs. Saxon still referred to him implacably as the little boy and followed all his activities with a distinctly chilly eye. Eve found this somehow surprising in the older woman. Ambrose was spoiled, certainly, but so spoiled as to be almost laughable; every time he opened his mouth he posed a challenge.

All that was visible of him when Eve crossed the shadowed grass was one arm and his sneakered feet; the rest of him was engulfed in an enormous conical straw hat someone had brought Eve from Bermuda. Squatting absorbedly, crooning to himself, Ambrose was daintily bringing a chrysanthemum down to ground level with a pair of manicure “scissors.

“Reeds,” he said in his sweet precise voice as Eve took away the scissors.

“They’re not weeds, they’re flowers.” Would it be advisable to show him some real weeds, and let him—? No. “I wish you wouldn’t wear that hat,” said Eve.

Ambrose settled the hat firmly over his shoulders, and, head back so far that the fringe fell only to his nostrils, gazed combatively up at her through the mild October light. “I get sunburn,” he said.

Perhaps because he was an only and much-cosseted child, Ambrose had for his own person the deep reverence of a patriot for the flag. His shrieks at the smallest injury were of genuine horror, and at the end of every day he examined his collection of scratches and mosquito bites much more lovingly and anxiously than any mother could have done. He was kind enough to confide his findings to Eve—or at least she supposed he did; although his enunciation was that of a grammarian he made up some very odd words.

He was now blinking his long pale blue eyes at her from behind the disconcerting wisps of straw. “Saxon took my rockles,” he announced.

“Mrs. Saxon,” corrected Eve hastily. Too late, she realized that this implied agreement, although she had no idea of what Ambrose’s rockles might be. For that matter, Mrs. Saxon, who shared her husband’s all-embracing fears of catastrophe and had no grasp of the immense deference in which Ambrose held himself, did take a great many things away from him; she seemed to have a belief that small boys should be neat, clean, silent, and totally safe at all times.

“Mississaxon,” sang Ambrose trippingly and, liking the sound of it, raised his voice and tried it a few more times. From the corner of her eye, as she shushed him, Eve caught the sharp turn of Iris’s head behind the kitchen window and knew, in an instant of discernment, where the friction lay. Philadelphia-bred, used to considerable material comfort until her marriage and the long slow progress to desperate poverty—Eve knew this from Jennifer Morley, the wife of the real estate broker who had found her this house—Mrs. Saxon could be casual and humorous while doing domestic work for the first time in her life in the society of her peers. It was the presence of an odd and noticing child like Ambrose that made her feel betrayed and demeaned.

The conical hat slipped forward, obscuring Ambrose to the waist. Emerging from it, turning a deep executive red, he shouted, “I want my rockles!” and partly to mollify him, partly because she felt awkward in the face of Iris Saxon’s grief over the dead Mrs. Pulliam and would just as soon not go back into the house just yet, Eve submitted her hand to his imperious tug.

Her own reflection in a window caught her briefly by surprise: a fair-haired girl whose face was perhaps too thin, companioned by an animated hat. For just an instant the child, the grass, the little adobe house swam together in a dizzying reversal of the this-has-happened-before feeling. The background of six months ago was the real and solid one, and this some strange projection of the mind . . .

She was living, this other Eve Quinn, in an apartment in a glass-and-concrete structure which glowed with pride at being all of six stones high. She was a copywriter with the advertising firm of Cox-Ivanhoe, and she was engaged, except for the ring, to William Harper Cox, who had been transferred from the Chicago office.

It had been a rapid courtship, and it should not have come as a jolt to Eve when, along with the ring, came William Harper Cox’s insistence on a wedding in the almost-immediate future. He was more businesslike than ardent about it; his manner said, “All right, we’ve had the preliminaries, now let’s get on with it.” Eve began to feel a little like a piece of necessary furniture for which, if he could not have delivery at once, the impatient would-be buyer would shop elsewhere.

Inevitably, because

Bill was not a good dissembler, it emerged that he had been promised a vice-presidency in the firm by his uncle, the ruling Cox, only when he gave evidence of having “settled down’’; in his case, this implied the married state. Eve knew that he was certainly very attracted to her, possibly even in love with her. It was also possible that as a husband he would be as steady as a rock, and that they would both be able to dismiss and forget forever this underlying factor in their marriage.

Someone else might have managed it. Punctiliously, and to the obviously genuine regret and embarrassment of old Mr. Cox, Eve resigned from the agency. She reflected, as she cleaned out her desk and found a favorite compact for which she had been conducting periodic hunts in her apartment, that the curiosity of the rest of the copy department about the dissolving of this happy and handsome match was almost pitiable. The secretaries, it was clear, were thinking in terms of some vengeful female turning up on Eve’s doorstep, complete with waif.

Was the truth better, or very slightly worse?

The mood of detachment did not last; she quickly discovered the very sound basis in reason for the trips abroad taken by broken-hearted young women of another day. She was not broken-hearted, but she felt almost physically damaged from head to foot—perhaps because that was where pride lay, she thought ironically—and she was in violent rebellion against the surroundings and the friends who had been the witnesses of her naive and tranquil happiness. Her perusal of the real estate columns and eventual contact with Richard Morley, who found her the house in the Valley, dropped her into another world.

It was a rented house on a cottonwood-shadowed corner, surrounded by an adobe wall and big enough only for a single person who liked elbow room or a childless married couple. Single people usually preferred apartments and wives felt strongly about built-in kitchens and closet space, neither of which was a strong point of the house. But it had a step-down living room with a curved corner fireplace and one whole wall of bookshelves, and its windows were set so low that an apricot and a plum tree and wildly neglected grass seemed part of the interior. Eve took it at once.

Somewhat to the mystification of Richard Morley, she was uncomplaining about the dilapidated state of the house; she wanted to be fiercely busy, and she was. With the help of Iris Saxon, whom Jennifer Morley enlisted on her behalf, she got the tall windows curtained, the kitchen shelves papered, the brick floors clean and shining.

On an evening when everything had been done, and lamplight touched the cool white walls and folds of blue toile in the living room, Eve was seized by something close to panic. She had been in the middle of writing a resume which she would send to the other advertising agencies in the city; she ripped the sheet out of the typewriter and wrote instead to her first cousin Celia Farley in New York, inviting her and her son Ambrose to come out for a visit.

She and Celia had grown up together, and were more like sisters then cousins. Eve had never met Roger Farley, but knew from Celia’s sporadic letters that he was just finding his feet in a brokerage house and couldn’t take any time away. But Celia, and Ambrose . . . ?

Celia was delighted. They came, and Eve moved into the tiny space which had to serve as a guest bedroom. By day she drove them up on the mesas, to Santa Fe, to nearby pueblos; by night, with Ambrose asleep, they caught up the threads of distant relatives remembered only from long-ago weddings and funerals.

‘“Does anybody know what happened to Eugene?”

“Yes, he finally married that girl with all the teeth and the mountains of hair.”

“And the Kerrigans’ uncle—was it Patrick?”

Celia rolled her eyes upward. “There’s a bounty on the head of whoever finds him.”

They had been there two weeks when Celia, on the diving board at the local indoor pool, called, “I wonder if I can still do this?” and tried to execute a double back flip and broke her back.

The confusion at the pool, with Ambrose screaming distractedly; the long-distance call to Roger, his distraught arrival and understandable glance of ferocity at Eve, the indirect author of this crisis: all Eve remembered of it very clearly was standing in the hospital corridor and saying to Roger, “I know you want Celia back in New York with her own doctor, but I’d be glad to keep Ambrose out here with me until things get straightened out a little.”

She knew that a considerable amount of money, or some rallying relatives, might have taken care of the situation. Celia and Roger did not have the money, and Rogers mother, who lived with them in the apartment on Sixty-first Street, was in a wheelchair. And if Eve had not invited Celia to Albuquerque, had not taken her to the swimming pool . . .

. . . Ambrose stayed.

With all this dashed briefly against her consciousness and then falling away like water from glass, Eve realized that Ambrose had halted and was pointing at the weathered tool shed at the very back of the circumscribed grounds. “Rockies,” he said expectantly, and then greater volume, “I want my rockles.”

In the same firm tone Eve answered, “Well, that’s one place they aren’t, Ambrose.”

He could not possibly have wandered into the tool shed; Eve had seen to that by attaching a padlock because of the sickle and other tools there, the moist cobwebby darkness with its possibilities of spiders or worse. Eve was not too far away from her own childhood to realize that for lack of a contemporary to say, “I dare you,” Ambrose might well say, “I dare me,” out of a combination of swagger and deep fright. Certainly, having dragged her so insistently to the tool shed, he had a curiously riveted stance. He wanted his mysterious treasure, but he wanted Eve to get it.

She had her own distaste for the shed; on her last visit there, in search of grass clippers, a furry black spider had leaped nimbly onto her wrist. She said with great firmness, “You can’t possibly have left anything in there, Ambrose. Come on, it’s almost time for your bath . . .”

It seemed odd, looking back, that no chill invaded the innocent, bird-twittery sunlight, and that the usually indeflectable Ambrose simply rammed the hat down farther over his person and said no more on the subject.

With the night came the wind; it was going to be an early autumn. In the house that had been tramped through and photographed and stared at by avid sightseers, Arthur Pulliam, managing to look like a photograph from an old album even in his pajamas, lay in bed and gazed at the ceiling. He did not part his hair in the middle or wear steel-rimmed glasses, but he gave that impression. His thoughts were very much his own.

A few miles away, Richard Morley had also gone to bed, after saying gently and unavailingly to his wife, “It’s getting late, you’re tired . . Jennifer Morley shook her head and went on regarding her book without seeing it. When the bedroom door had remained closed for fifteen minutes she went quietly to the telephone; her implacable, untouchable politeness had been replaced by a look of tense concentration. She dialed. She said very softly, “Mr. Conlon? Is this by any chance the Henry Conlon . . . ?”

Eve Quinn and Ambrose were fast asleep, Ambrose having been deprived of the monstrous hat in which he had retired and been discovered by Eve scarlet and heavily bedewed. It lay beside him on his pillow, a long neatly folded triangle with a dripping fringe.

On a very different kind of pillow, in the county jail, and oblivious from an entirely different cause, reposed a man whom the patient combings into the murder of Molly Pulliam had turned up: a yardman who had worked for the Pulliams several months ago and been discharged for theft. He had been heard to mutter vengefully. He was presently in a state of drunkenness dangerously akin to coma.

The Saxons were preparing for bed, having been made late by having to cash Eve Quinn’s check and being caught in a long line at the supermarket where they shopped. The wind seemed viciously loud around their small apartment with its occasional startling incongruity; a beautiful old lace cloth which had belonged to Iris’s mother dipping its fragility over a scarred formica table; a small painted figurine bought on a trip to Italy.

Iris Saxon was

braiding her hair; Ned, of necessity only a few feet away, was polishing glasses with a fanatical eye, holding them up to the bare ceiling bulb, polishing them again. He stopped suddenly and listened. “What’s that?”

A year ago, Iris Saxon would have said tranquilly, “Oh, the wind.” Now she listened as tensely as her husband. There was a rustle of leaves outside, the progress of a dog to other ears, but Ned Saxon instantly darkened the light, and moving swiftly for so bulky a man, snatched up a heavy flashlight and let himself softly out into the night.

A drug ring, Iris had come to believe. Silent and terrible strangers who used the path beside their apartment to convey marijuana or worse to the people who lived across the street, the people who came and went at all hours and often woke the Saxons out of their much-needed sleep. A small voice deep in Iris’s memory remarked that there could be other and innocent reasons for such behavior, but it was easily stilled.

Ned Saxon came in, breathing heavily and angrily. “Got away again, darn it. I’ll rig up a trip wire out there tomorrow, and then we’ll see how slippery they are.” He gazed anxiously at Iris, now in bed, her long graying braids surprisingly childish on the pillow. “Tired?”

“Not really . . . it’s been such a shock about poor Molly. You know, I can still hardly believe it.”

“It was a shock all right,” said Ned soberly. “You remember, when you first started going there, how I warned Arthur Pulliam that he ought to keep a big dog around a place like that? Asking for a robbery, in that neighborhood, but of course he knew best . . .”

Iris had drifted off to sleep. Ned pulled the blankets protectively close about her and went to bed himself. The last lamp, just before he switched it off, shone on his creamy-orange head.

4

A HEADLINE in the morning paper said, “Pulliam Slaying Suspect Found Dead in Cell.” An autopsy had been ordered to determine the cause of death.

Don't Open the Door

Don't Open the Door